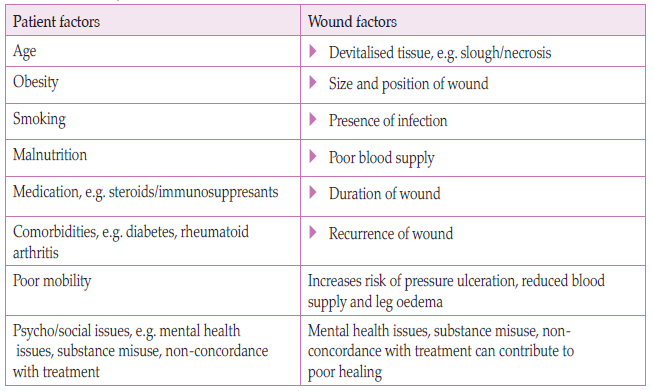

Wounds that fail to heal or show significant progress after four weeks, despite optimal treatment, have traditionally been classified as ‘chronic’ wounds (Doughty and Sparks-DeFriese 2016; Murphy et al, 2020). However, more recently, it has been suggested that the term ‘chronic wound’ be replaced with ‘hard to heal’, emphasising the possibility of overcoming barriers to healing and shifting the perspective towards a more optimistic outlook for wounds that are slow to heal (Murphy et al, 2020). Several factors can contribute to impaired healing (Table 1), and effective management requires clinicians to conduct holistic assessment, identifying and addressing underlying barriers to healing whenever possible (Wounds UK, 2018). Failure to do so can lead to unwarranted variations in care and increased reliance on non-evidence-based practices, further exacerbating the burden of hard-to-heal wounds (Gray et al, 2018).

The significant economic burden of hard-to-heal wounds is well documented (Wounds UK, 2018; Guest et al, 2020). A study by Guest et al (2020) estimated that approximately 3.8 million wounds are treated annually in the UK, with an associated cost of £8.2 billion per year. Notably, 81% of these wounds are managed in community settings, placing substantial demand on resources such as district nurse visits, practice nurse appointments, and costs associated with wound dressings. Additionally, the study found that the healing rate for chronic wounds was around 59% when no infection was present. This economic burden is expected to rise in the coming years due to an ageing population with increasingly complex comorbidities (Guest et al, 2020).

The burden of hard-to-heal wounds extends beyond financial and resource constraints. Patients with non-healing wounds often experience a significant decline in quality of life, facing challenges such as sleep disturbance, pain, mental health issues, and social isolation. This list is not exhaustive and each patient with a wound will have a different experience — an important consideration when developing an individualised plan of care (Wounds UK, 2018).

The significant economic burden of hard-to-heal wounds is well documented (Wounds UK, 2018; Guest et al, 2020). A study by Guest et al (2020) estimated that approximately 3.8 million wounds are treated annually in the UK, with an associated cost of £8.2 billion per year. Notably, 81% of these wounds are managed in community settings, placing substantial demand on resources such as district nurse visits, practice nurse appointments, and costs associated with wound dressings. Additionally, the study found that the healing rate for chronic wounds was around 59% when no infection was present. This economic burden is expected to rise in the coming years due to an ageing population with increasingly complex comorbidities (Guest et al, 2020).

The burden of hard-to-heal wounds extends beyond financial and resource constraints. Patients with non-healing wounds often experience a significant decline in quality of life, facing challenges such as sleep disturbance, pain, mental health issues, and social isolation. This list is not exhaustive and each patient with a wound will have a different experience — an important consideration when developing an individualised plan of care (Wounds UK, 2018).

Factors contributing to chronicity include:

Additionally, limited access to wound care training and education can contribute to suboptimal care, ultimately leading to poorer patient outcomes (Grothier, 2018; Wounds UK, 2018; Atkin, 2020).

- Failure to conduct accurate clinical assessment and reach a correct diagnosis

- Failure to treat underlying comorbidities that contribute to poor healing

- Lack of engagement with the multidisciplinary team (MDT) to assist in managing complex care (e.g. vascular specialists, dieticians, physiotherapists, psychologists, tissue viability nurses)

- Patient compliance

- Use of non-evidence based practice

Additionally, limited access to wound care training and education can contribute to suboptimal care, ultimately leading to poorer patient outcomes (Grothier, 2018; Wounds UK, 2018; Atkin, 2020).

The potential of a wound to become chronic or hard to heal should be identified via holistic assessment (Wounds UK, 2018). For these patients, access to appropriate advanced therapies is gaining great interest with the possibility of increasing healing potential (European Wound Management Association [EWMA], 2008; Piaggesi et al, 2018). Advanced wound therapies, such as negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), oxygen therapy, electrical stimulation, medications, growth factors, and cellbased therapies (among others), may initially appear more costly (EWMA, 2008). However, if they contribute to faster healing rates, they could prove to be more cost-effective in the long run (EWMA, 2008; Piaggesi et al, 2018). Ongoing research continues to assess their efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and optimal use in clinical practice to ensure that they are applied appropriately and deliver the best patient outcomes (Piaggesi et al, 2018).

This article discusses the findings of a survey to healthcare professionals (HCPs) to establish their current perspectives on wound care provision in their field of practice and identify some of the challenges that are faced in clinical practice. It also highlights their views and use and acceptability of advanced wound therapies.

This article discusses the findings of a survey to healthcare professionals (HCPs) to establish their current perspectives on wound care provision in their field of practice and identify some of the challenges that are faced in clinical practice. It also highlights their views and use and acceptability of advanced wound therapies.

AIM

A survey was conducted to gain a deeper insight into the challenges and attitudes of HCPs when treating hard-to-heal wounds, and to determine opinions of advanced wound therapies.METHOD

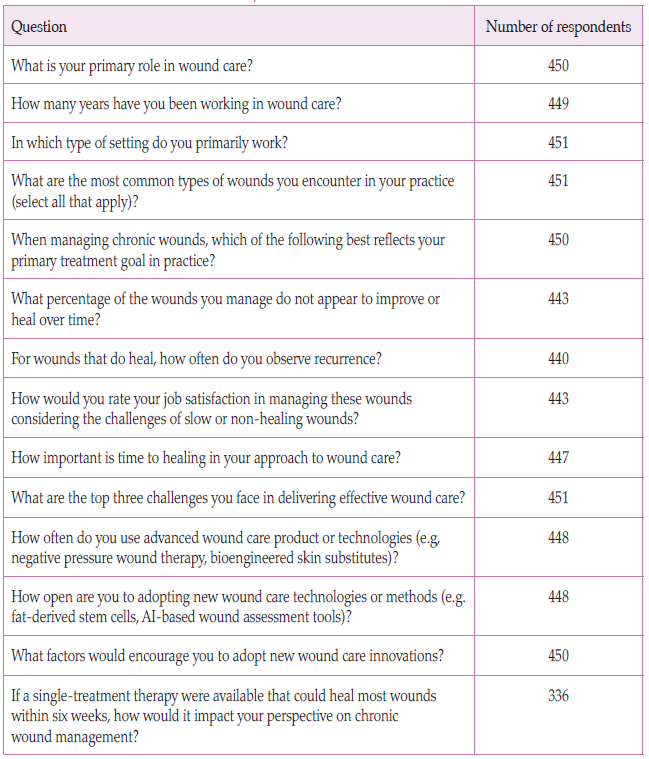

The survey consisted of 14 questions (13 had fixed answers with one having an opened-ended option), and opted-in users of the Journal of Community Nursing (JCN) website were invited to take part via an e-newsletter link. The survey was available between 8–22 January, 2025. Results were collated automatically using survey software and crossreferenced to data gathered in excel.

Table 1: Factors that can contribute to poor wound healing (adapted from Wounds UK, 2018; Atkin, 2022; Grey and Patel, 2022)

RESULTS

Over the period of the survey (two weeks), a total of 451 HCPs responded. However, it should be noted that not everyone answered all 14 questions so numbers (n) of respondents may vary according to the question (Table 2). Responses to the questions are now presented.Primary role in wound care

Participants were asked to describe their current role or job position. The most common role was general nurse (29%, n=129). Specialist nurses, including district and practice nurses, accounted for 26% (n=119), while tissue viability nurses (TVNs) made up 14% (n=65). Healthcare assistants comprised 6% (n=26), and physicians represented 1% (n=5). Additionally, 23% (n=106) of participants selected ‘other’ as their job role, which included various nursing positions such as nursing associates, student nurses, nurse practitioners, dermatology nurses, palliative care nurses, and homeless practitioners. The survey also included responses from podiatrists and foot health specialists, highlighting the diverse range of disciplines and healthcare settings represented.Number of years working in wound care

A significant portion of respondents had over 10 years’ experience of delivering wound care (49%, n=222), while 28% (n=127) had been working in the field for one to five years, suggesting a considerable level of expertise among the clinicians surveyed. Additionally, 18% (n=79) had six to 10 years of experience, and a smaller group (5%, n=21) had less than one year’s experience.Primary place of work

The majority of respondents worked in community care (41%, n=187), with acute care represented by 30% (n=135). 11%(n=50) worked within long-term care, which included nursing homes, and 17% (n=79) worked in other areas of healthcare.Most common types of wounds encountered in practice

Pressure ulcers were the most frequently encountered wound type, reported by 67% (n=305) of respondents. Venous leg ulcers followed closely at 63% (n=284), while surgical wounds were seen by 60% (n=271). Diabetic foot ulcers were reported by 52% (n=237), and arterial ulcers by 34% (n=154). Additionally, 18% (n=83) of respondents commonly encountered other wound types, including traumatic wounds, skin tears, malignant fungating wounds, and self-harm wounds.Primary treatment goal when managing chronic wounds

The primary treatment goal reported by most respondents (82%, n=371) was a combination of achieving complete wound healing through tissue regeneration and closure, while also managing symptoms such as exudate control, maintaining skin health, reducing odour, and improving quality of life. A smaller proportion (9%, n=42) focused solely on achieving complete wound healing, while 6% prioritised symptom management as their main goal.

Table 2: Questions and number of respondents for each

Percentage of wounds that did not appear to improve or heal

A high proportion of respondents (63%, n=281) reported that 0–25% of the wounds that they managed did not heal or improve over time. A slightly lower proportion (23%, n=101) indicated that 25–50% of wounds failed to heal or improve. A minority (10% n=46) stated that 50–70% of their managed wounds did not heal, while 3% (n=15) reported that 75–100% of wounds failed to show improvement or heal over time.Recurrence observed in wounds that healed

Recurrence was most commonly reported in up to 25% of wounds, as indicated by 56% (n=241) of respondents. For 25–50% of wounds, recurrence was reported by 34% (n=148). Additionally, 8% (n=36) experienced recurrence in 50–75% of wounds, while 2% of respondents reported recurrence in 75–100% of wounds.Job satisfaction considering the challenges faced when managing hard-to-heal wounds

Many of the respondents (63%, n=281) indicated that they were somewhat satisfied with the management of hard-to-heal wounds, acknowledging that while they handled the challenges well, the process could sometimes be frustrating. Meanwhile, 28% (n=123) reported feeling confident and fulfilled in their role expressing job satisfaction despite the challenges. A smaller percentage found that the challenges arising in caring for people with hard-to-heal woundsmade their job less rewarding (8%, n=27), while 2% (n=11) stated that these challenges had a negative impact on their overall job satisfaction.

Importance of time to healing in respondents’ approach to wound care

Half of the respondents (50%, n=223) believed that healing time was very important and a key factor in their approach to wound management, although not the sole focus. Meanwhile, 31% considered healing time to be extremely important and a top priority. Additionally, 21% (n=93) stated that while healing time was somewhat important, other factors were equally significant. Only 2% (n=8) indicated that healing time was neither important, nor a primary consideration.Top three challenges faced when delivering effective wound care

An overwhelming 69% (n=311) of respondents identified lack of time and resources as the primary challenge to delivering effective wound care. Patient compliance was also a significant concern, cited by 67% (n=303). Additionally, 47% (n=211) highlighted limited access to advanced therapies, while 37% (n=169) reported insufficient training and education as a challenge. Cost pressures were also a factor, noted by 32% (n=145) of respondents. Additionally, 11% (n=50) indicated that there were other challenges such as patients at the end of life, communication with other HCPs, and poor availability of appropriate dressings, which proved challenging to delivery of effective care.

Use of advanced wound care products or technologies

Some respondents (39%, n=176) indicated that they occasionally used advanced wound care products in selected cases. Meanwhile, 27% (n=120) reported rarely using them, and 21% (n=93) stated that they never used advanced products Only a small percentage (13%, n=59) frequently incorporated advanced wound care products into their practice.Openness to adopt new wound care technologies or methods

There were 45% (n=200) of respondents that were very open to adopting new wound care technologies, 27% (n=120) were somewhat open and 25% (n=110 were neutral. A small proportion were either somewhat resistant (4%, n=16) or very resistant (0.45%, n=2) to adopting new wound care technologies.Factors which would encourage adoption of new wound care innovations

The leading factor encouraging participants to adopt new wound care innovations was strong evidence of clinical efficacy, cited by 88% (n=396) of respondents. Training and education were also highly valued, with 82% (n=370) considering them important. Other key factors included ease of use (69%, n=312), cost-effectiveness (68%, n=306), and support from management (66%, n=298). In contrast, patient demand was only considered important by 34% (n=153) of respondents.Impact on chronic wound management if a singletreatment therapy could heal wounds within six weeks

This question allowed respondents to provide free-text responses about the potential impact of a single-treatment therapy capable of healing most wounds within six weeks. While 5% (n=17) were sceptical, doubting whether such a treatment could exist or effectively aid in chronic wound management, the overwhelming majority (95%, n=319) believed it would be highly beneficial. Many described it as ‘amazing’, ‘brilliant’, and a ‘game changer’, emphasising its potential to significantly improve patient outcomes, reduce nursing visits, and lower overall healthcare costs.DISCUSSION

The majority of respondents worked within the community setting (41%), which is not surprising since most wound care is thought to be delivered in the community (Guest et al, 2020).The most common wound types encountered by respondents was similar to other studies exploring wound aetiologies (Gray, 2018 et al; Guest et al, 2020), and included pressure ulcer, venous leg ulcers and diabetic foot wounds. These wounds are also the most commonly cited wounds linked to chronicity, usually as a consequnece of underlying pathological processes (Pignet et al, 2024). While issues surrounding non healing of chronic wounds have been previously discussed, for some patients, due to their complexity, wound healing may not be an appropriate outcome and understanding what is important to them and managing symptoms becomes the priority, rather than healing (EWMA, 2008). This was reflective in respondents’ responses where just 10% indicated that wound healing was the only primary goal. Most respondents (82%) felt that their primary goal was a balance between achieving complete wound healing and managing symptoms such as exudate volume, skin health maintenance, odour reduction, and improving the individual’s quality of life. This is a crucial consideration, as HCPs’ goals may differ from those of patients (Trouth, 2024). Aligning care with patient priorities fosters coproduction and enhances compliance, which can ultimately influence the healing process (Trouth, 2024), and is also a key component of true evidence-based practice.

Healing rates among respondents varied, with 63% reporting that only 0–25% of wounds failed to heal, while 37% indicated that 25–100% of treated wounds did not heal over time. Further investigation is needed to determine whether this is associated with specific wound types, the role of the respondent (e.g. end-of-life settings would aim for symptom control), or other factors that may influence healing. Similar findings however were reported in a study by Guest et al (2020), which found that only 59% of chronic wounds without infection healed within the study period, dropping to 45% when infection was suspected.

Recurrence rates were reported in less than 25% of patients by 56% of respondents; however, 44% experienced high recurrence rates. While this survey did not investigate which wound types were most prone to recurrence, Rosenblum et al (2017) highlighted that recurrence within six months of healing remains a significant issue, affecting 40% of leg ulcers and diabetic foot wounds — a possible effect of the underlying condition for which there is no cure.

Respondents indicated that they faced several challenges when trying to deliver effective wound care, with 69% citing a lack of time and resources as the primary barrier. Patient compliance (67%), limited access to advanced therapies (47%), insufficient training (37%), and cost pressures (32%) were also a significant concern. Atkin (2020) emphasised that wound care places a significant demand on NHS resources, yet is often overlooked and does not always receive the recognition or support needed for effective management. Grothier (2018) indicated that evidence-based clinical guidance in wound care often could not be implemented due to lack of resources leading to frustration in HCPs trying to deliver effective wound care. Additionally, wound care education is frequently deprioritised in the face of resource challenges, such as staff shortages (Grothier, 2018; Atkin, 2020).

Given the substantial financial pressures on the NHS, it is more crucial than ever to implement strategies that promote cost-effective, evidence-based care (Gray et al 2018). Grothier (2018) also identified patient concordance as a significant challenge in wound care. Overcoming non-concordance can be difficult, but may be improved through a patientcentred approach that emphasises engagement and education (Grothier, 2018; Wounds UK, 2018).

Despite the challenges, most respondents (63%) felt somewhat satisfied or very satisfied (28%) with their ability to manage hard-to-heal wounds, although some found the process frustrating.

Use of advanced wound care products varied, with 39% of clinicians using them occasionally, while 27% rarely use them, and 21% never do. Only 13% frequently incorporate these products into their practice. The adoption of new wound care innovations is primarily driven by strong clinical evidence (as indicated by 88% of the survey respondents) and training and education (82% of the survey respondents). Other influencing factors include ease of use (69%), cost-effectiveness (68%), and management support (66%), while patient demand plays a lesser role (34%). Anecdotally, access to advanced wound care products may be influenced by knowledge and expertise of the clinician and availability and cost of the product. AI technologies, such as digital wound solutions that assist in assessment, have gained interest in the past few years and certainly can contribute to increasing the accuracy of wound assessment and diagnosis (Piaggesi et al, 2018), if their validity and reliability is established.

If a single-treatment therapy capable of healing most wounds within six weeks was available, 95% of respondents believed it would be a game-changer, improving patient outcomes, reducing nursing visits, and lowering healthcare costs. There was great interest shown by respondents to know if such a therapy existed and many wanted to know more about the therapy and the evidence that supported its use in clinical practice.

LIMITATIONS

The survey was distributed through the JCN to its members, which may have excluded other HCPs who treat wounds but do not have access to the JCN site. Thus, the findings potentially may not represent the views of the broader healthcare population. Nevertheless, the respondents comprised a diverse range of healthcare professionals, from various healthcare settings, providing a good overview of wound care provision across different clinical environments. A further limitation was that answers were not stratified according to professions, which could have given further insight into jobspecific challenges and opinions.

Some survey questions required participants to estimate figures, such as the recurrence rate of wounds or the proportion of wounds that fail to heal or improve over time. This introduces a degree of subjectivity and the possibility of recall bias. Future research could involve collecting this data directly from caseload managers for greater accuracy, although this approach would be more time-consuming and may require ethical approval.

Despite these limitations, the survey provided a convenient and accessible method for engaging a large number of participants. It offered valuable insights into current wound management practices and highlighted key challenges faced by a wide range of HCPs working in wound care today.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the survey reported here provide a window into the views of and challenges faced by HCPs working in wound care, which are in alignment with published papers on the burden of wound care (Guest et al, 2020). Many HCPs reported significant challenges in delivering evidencebased care, including resource constraints, limited access to training and advanced wound therapies, patient non-compliance, and financial pressures. Despite these difficulties, many HCPs expressed high job satisfaction. Recurrence and non-healing were commonly encountered, with many lacking access to advanced wound care products or technologies but expressing a willingness to adopt them if they were readily available and training was provided. Addressing the challenges of hard-to-heal wounds requires a shift towards evidence-based practice, enhanced clinician education, and early intervention strategies to improve healing rates, reduce healthcare costs, and enhance patient quality of life.

The survey discussed in this article was supported by Paracrine.

References

Atkin L (2020) Education in wound care: the need to improve access. J General Practice

Nurs 6(1): 37–41

Doughty D, Sparks-DeFriese B (2016) Wound Healing Physiology. In: Bryant RA, Nix D, eds. Acute and Chronic Wounds: Current Management Concepts. 5 edn. Elsevier, St Louis: 67–72

European Wound Management Association (2008) Position Document: Hard to Heal

Wounds: a holistic approach. MEP Ltd, London

Gray TA, Rhodes S, Atkinson RA, et al (2018) Opportunities for better value wound care: a multiservice, crosssectional survey of complex wounds and their care in a UK community population. BMJ Open 8: e019440

Grothier L (2018) what are the challenges for community nurses in implementing

evidence-based wound care practice? (part 1 ). Wounds UK 14(4): 18–23

Guest JF, Fuller GW, Vowden P (2020) Cohort study evaluating the burden of wounds to the UK’s National Health Service in 2017/2018: update from 2012/2013. BMJ Open 10: e045253

Murphy C, Atkin L, Swanson T, et al (2020) Defying hard-to-heal wounds with an early antibiofilm intervention strategy: wound hygiene. J Wound Care 29(Suppl 3b): S1–28

Piaggesi A, Lauchli S, Bassetto F, et al (2018) Advanced therapies in wound management: cell and tissuebased therapies, physical and biophysical therapies smart and IT based

technologies. J Wound Care 27(sup6a): S1–S137

Pignet AL, Schellnegger M, Hecker A, Kamolz L-P, Kotzbeck P (2024) Modeling wound chronicity in vivo: the translation challenge to capture the complexity of

chronic wounds .J Invest Dermatol 144(7): 1454–70

Rosenblum J, Gazes MI, Rosenblum S, Karpf A, Greenberg N (2017) A multicentre

evaluation of chronic ulcer recurrence with the use of varying mechanical wound healing modalities. J Vasc Med Surg 5(3): 1000323

Trouth S (2024) Introducing Wound Balance: placing the patient at the heart of wound

healing. Wounds UK 20(1): 32–7

Wounds UK (2018) Best practice statement: Improving holistic assessment of chronic

wounds. Wounds UK Available to download from: www.wounds-uk.com

Nurs 6(1): 37–41

Doughty D, Sparks-DeFriese B (2016) Wound Healing Physiology. In: Bryant RA, Nix D, eds. Acute and Chronic Wounds: Current Management Concepts. 5 edn. Elsevier, St Louis: 67–72

European Wound Management Association (2008) Position Document: Hard to Heal

Wounds: a holistic approach. MEP Ltd, London

Gray TA, Rhodes S, Atkinson RA, et al (2018) Opportunities for better value wound care: a multiservice, crosssectional survey of complex wounds and their care in a UK community population. BMJ Open 8: e019440

Grothier L (2018) what are the challenges for community nurses in implementing

evidence-based wound care practice? (part 1 ). Wounds UK 14(4): 18–23

Guest JF, Fuller GW, Vowden P (2020) Cohort study evaluating the burden of wounds to the UK’s National Health Service in 2017/2018: update from 2012/2013. BMJ Open 10: e045253

Murphy C, Atkin L, Swanson T, et al (2020) Defying hard-to-heal wounds with an early antibiofilm intervention strategy: wound hygiene. J Wound Care 29(Suppl 3b): S1–28

Piaggesi A, Lauchli S, Bassetto F, et al (2018) Advanced therapies in wound management: cell and tissuebased therapies, physical and biophysical therapies smart and IT based

technologies. J Wound Care 27(sup6a): S1–S137

Pignet AL, Schellnegger M, Hecker A, Kamolz L-P, Kotzbeck P (2024) Modeling wound chronicity in vivo: the translation challenge to capture the complexity of

chronic wounds .J Invest Dermatol 144(7): 1454–70

Rosenblum J, Gazes MI, Rosenblum S, Karpf A, Greenberg N (2017) A multicentre

evaluation of chronic ulcer recurrence with the use of varying mechanical wound healing modalities. J Vasc Med Surg 5(3): 1000323

Trouth S (2024) Introducing Wound Balance: placing the patient at the heart of wound

healing. Wounds UK 20(1): 32–7

Wounds UK (2018) Best practice statement: Improving holistic assessment of chronic

wounds. Wounds UK Available to download from: www.wounds-uk.com